aaa

aaa

While the medieval period in England is typically dated from 1066 to 1485, Oxford’s story begins earlier. Let’s first step back into the Early Medieval period, between 410 and 1066.

Following King Sweyn Forkbeard and the Vikings’ raids of the early 11th century, Oxford had become prosperous. It was a place where Witans, councils of the King, were convened and was notably where King Cnut, Sweyn’s son, was able to forge peace between the Danes and Saxons, establishing his rule over England.[1]

At the time, the town had around 5,000 residents – although no exact numbers exist. Theorised figures suggest it would have made Oxford the sixth or seventh biggest town in the country at the time.[2]

However, by the completion of the Domesday Book in 1086, Oxford appears a bit worse for wear. Of the estimated 1,018 houses inside and outside the walls, 57% are listed as ‘waste’, meaning they generated no taxation.[3] This is the second highest in England, worse than much of the north, which had been famously harried by William the Conqueror’s army. The population also seems to have declined to between 1,000 and 2,000.[4]

Yet despite this, there is no evidence that Oxford was part of a rebellion against William, nor suffered his army’s wrath.[5] What actually happened is still unclear. Suggested causes include:

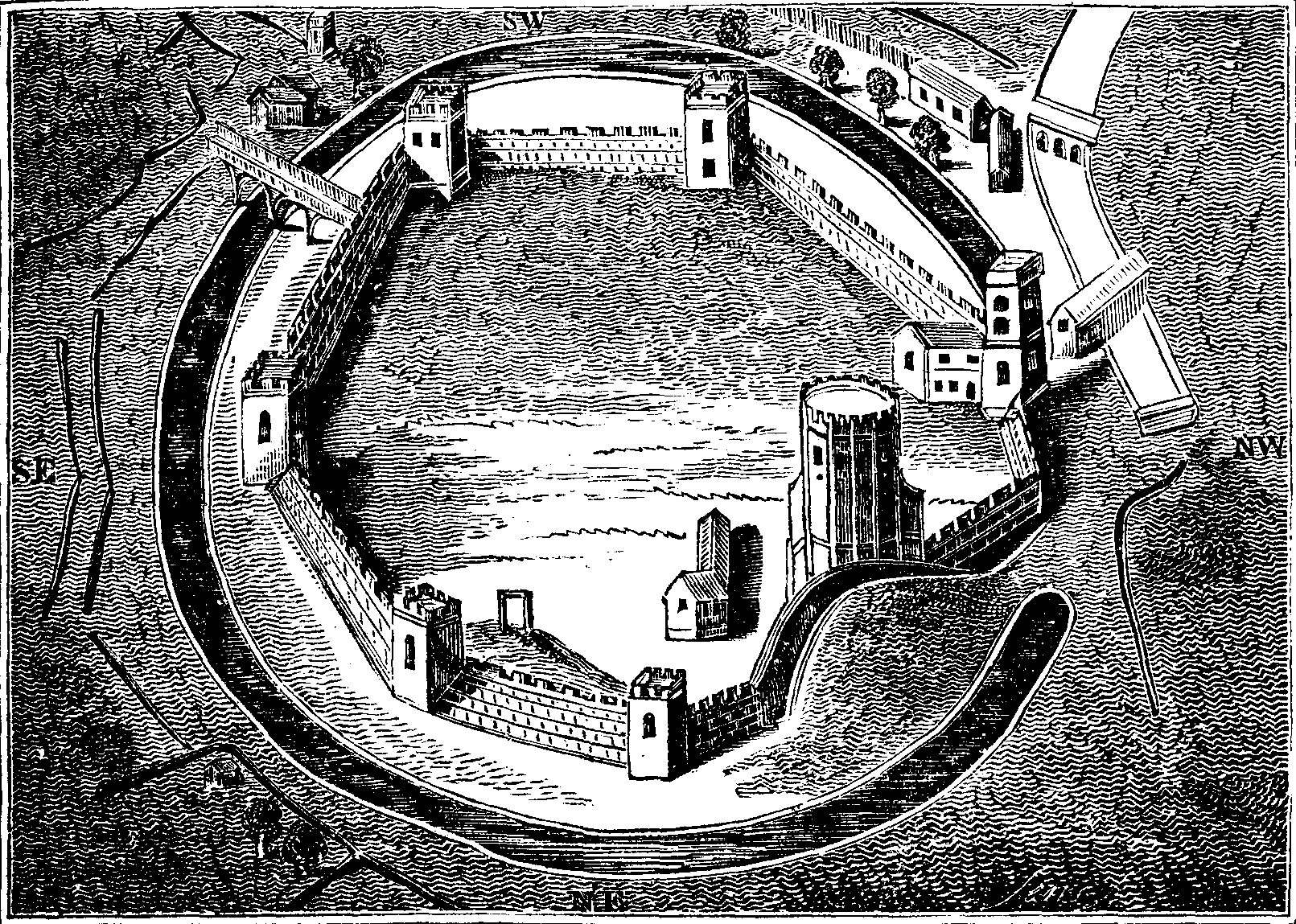

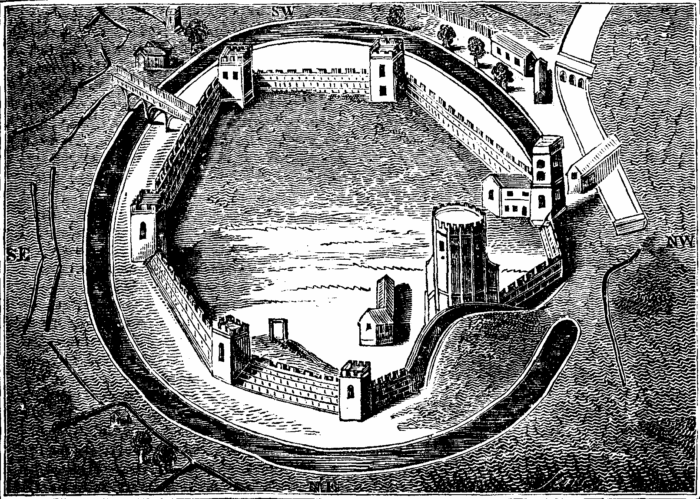

Regardless of cause, Oxford needed rebuilding, and that was left to its new Norman overlord, Baron Robert D’Oyly. Robert was a minor magnate back in Normandy, but he built a powerful political base in England. He married the daughter of Wigod, the Saxon lord of Wallingford, and, upon his death, inherited his lands in Berkshire and Oxfordshire.[10]

Appointed High Sheriff of Oxford in 1071, he got to work building across the town, in particular churches.[11] It was during this time that the Collegiate Church of St George was built in the castle, and pre-existing churches like St Michael’s in the Northgate and St Peter’s in the east were rebuilt.[12] He also built a prominent causeway called ‘Grandpoint’ where the Abingdon Road now is, which helped to make the Thames more easily fordable for trade.[13]

The rebuilding efforts of D’Oyly, plus a general recovery across post-conquest England, meant Oxford had returned to its prosperous self during the 12th century. It was such a prominent trade hub that a merchant guild formed, gaining trading rights in London that no other town in England had.[14] It also continued to play a large role in government affairs. King’s Councils continued to occur here throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, and royal apartments were maintained at Beaumont Palace for that purpose.[15]

The town’s importance could also be found at coronations, where its delegation sat alongside the far larger cities of London and Winchester.[16] This outsized role in the affairs of state, coupled with its prosperity, meant Oxford was granted a charter in 1155, giving it similar if not equal rights to those of London.[17] By 1227, it paid the third-highest taxation in the country, eclipsed only by York and London.[18]

Education also became a prominent part of the town. Teaching began in Oxford around 1096, but its importance rose as England came into increasing conflict with France.[19] Where previously English scholars had chosen to study abroad in Paris, they now had to do so at home, with Oxford being the natural choice. However, the growth of the university had some negative consequences for the town.

As land and buildings were bought up for colleges, the town lost important commercial areas. Rights were also lost as the university gained commercial and political powers, with the dispute between town and gown escalating into serious violence in the 14th century. The eventual outcome was the town losing these rights permanently and, as a result, becoming subordinate to the university.[20]

Combined with the Black Death, which likely killed a third of the town’s population, and the cloth industry shifting from urban to rural areas, Oxford’s fortunes drastically declined.[21] Its revenue fell relative to other towns in England. It ranked 8th in taxes paid to the government before the Black Death; it was 27th by the Tudor era.[22] The university suffered too, with fewer buildings rented by scholars and by the Tudor era, it was clearly declining as well. What had once been one of the most important economic centres in the country had become a minor town, albeit with a prominent university.

Its medieval roots, however, are still on full display at our site. Not only with our Castle Mound and crypt, but also St George’s Tower – once home to our very own Empress Matilda, one of the most important figures of this era!

[1] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford: A history of the city by Janet Cooper’, in Alan Crossley (eds), The Victoria History of the County of Oxford Volume IV, (London, 1979), p. 10.

[2] H. C. Darby, Domesday England, (Cambridge, 1977).

[3] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, p. 10.

[4] James Parker, The Early History of Oxford: 727-1000, (Oxford 1885), p. 233

[5] James Parker, The Early History of Oxford, pp. 186-200.

[6] James Parker, The Early History of Oxford, pp. 200-201.

[7] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, p. 10.

[8] Anne Dodd (eds), Oxford before the University, (Oxford, 2003), p.51

[9] Anne Dodd, Oxford before the University, p.51, Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, p. 10.s

[10] William Betham, The Baronetage of England, (London, 1802), p. 400. `

[11] James Parker, The Early History of Oxford, pp. 206-207.

[12] James Parker, The Early History of Oxford, pp. 215-217.

[13] Anne Dodd, Oxford before the University, pp. 53-56.

[14] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, p.35.

[15] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, pp. 12-13.

[16] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, p.9.

[17] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, p.50.

[18] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, p.12.

[19] Anne Dodd, Oxford before the University, p. 63.

[20] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, pp. 56-57.

[21] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, p. 19, 40.

[22] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford’, p. 15.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| PHPSESSID | session | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_UA-9822230-4 | 1 minute | A variation of the _gat cookie set by Google Analytics and Google Tag Manager to allow website owners to track visitor behaviour and measure site performance. The pattern element in the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. |

| _gcl_au | 3 months | Provided by Google Tag Manager to experiment advertisement efficiency of websites using their services. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _fbp | 3 months | This cookie is set by Facebook to display advertisements when either on Facebook or on a digital platform powered by Facebook advertising, after visiting the website. |

| fr | 3 months | Facebook sets this cookie to show relevant advertisements to users by tracking user behaviour across the web, on sites that have Facebook pixel or Facebook social plugin. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |