aaa

aaa

From saints to Trojan myths, uncover how ancient legends and history have entwined through the origins of Oxford.

Oxford as a city has been around for well over a thousand years, but tracing its exact foundations is murky, to say the least. The first true evidence of a place called Oxford existing is in the 10th century. In 912AD, as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle writes,

“This year died Ethered ealdorman of the Mercians; and King Edward took possession of London and of Oxford, and of all the lands which owed obedience thereto”.[1]

Whilst a clear statement showing that Oxford exists, this is not the year it was founded, as the town clearly already existed and was prominent by 912AD. This has led to much speculation about when Oxford truly came into existence. The well-known of these tales is that of St. Frideswide.

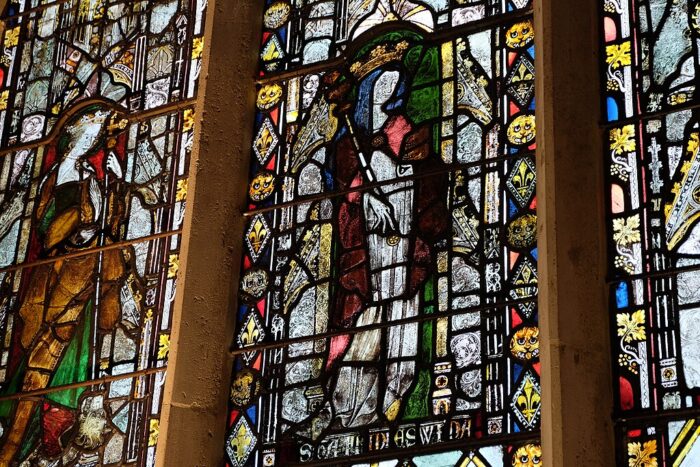

According to medieval writers, she was an Anglo-Saxon princess in the late 7th and early 8th centuries who refused to marry. Instead, she became a nun and founded a prominent church in an already present Oxford.[2] Unfortunately, the church was burned down during the St. Brice’s Day Massacre, but was rebuilt as a nunnery where Christ Church now stands today.[3]

It’s hard to determine much about Frideswide’s life – the only evidence we have comes from later histories, so whether she even existed is disputed.[4] However, some archaeological evidence would support the existence of a settlement in Oxford during her alleged time.

In particular, a cemetery located where Christ Church Cathedral now stands has been found to have started in the 8th century, around when Frideswide was said to have lived.[5] So, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume Oxford has an earlier history, perhaps being founded in the late 7th or 8th centuries, and perhaps by Frideswide.[6]

However, Frideswide and her church were not considered in the medieval era to be Oxford’s true origins. After all, the story claims she built a church in an already existing town. Geoffrey of Monmouth’s famous History of the Kings of Britain, written in Oxford, implies that Oxford existed far into the history of the ancient Britons.[7]

By the 15th century, ideas were being circulated that Alfred the Great had restored the university in 886AD, and brought it within the Saxon walls.[8] Assuming the university was restored in 886AD, it was believed by medieval historians that it must have existed before Alfred’s time.

From this, the idea of the “Greeklade” was formed – that ancient Greek philosophers accompanied the legendary Brutus and his Trojans to Britain, founding a place of learning that eventually morphed into the university north of Oxford and later restored by Alfred.[9]

This then culminated in a chronicle written by a priest called John Rous in the late 15th century. Rous was inspired by the History of the Kings of Britain and other records, but often elaborated and added to these stories, much to the annoyance of later historians.[10]

Rous claimed that in biblical times, there was a king called Mempric. He was a bad king, eventually torn apart by wolves for his wickedness, but one of the good things he did do was found a city called “Caer-Memre”.[11]

This city, according to Rous, morphed into becoming Oxford, and contained a centre of learning founded by Greek philosophers.[12]

None of the claims are verifiable, and no historian takes them seriously. However, scholars of the university at the time did take them seriously, mainly to prove they were better than Cambridge!

In 1564, Queen Elizabeth I visited Cambridge and a scholar there speaking at the queen’s visit claimed it to be “ancient and much more ancient than Oxford”.[13] These claims rested on the idea of a Spanish King Cantaber, who in a great conquest during his reign married the daughter of the King of the Britons and built a bridge called “Caergrant”, later becoming the town of Cambridge.[14]

It was claimed by Cambridge scholars that Cantaber had brought Greek philosophers and writers with him, starting the Greeklade in Cambridge, before being moved to Oxford at some later point.[15]

Ironically enough, Rous talks about both these myths as equally valid, though he would claim Oxford is the older university. This became the subject of fierce debate between the universities, though both sides quickly moved away from ideas of Cantaber or Mepric, as they were impossible to seriously prove.

Instead debate shifted towards whether Alfred had founded or restored Oxford’s university, which he hadn’t, but Cambridge found it hard to truly disprove at the time. As outlandish as they may seem, these ideas were not seriously debunked until the Victorian era, and University College would still claim King Alfred as their founder well into the Victorian era![16]

Though the city is not as ancient as the mythical Trojans, Oxford is still old with a tremendous amount of history.

At Oxford Castle & Prison, home to Oxford’s oldest secular building, St George’s Tower, we can still stand within a part of history that has witnessed the city’s growth and historic moments that shaped the country.

In the crypt of St George’s Chapel, Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote The History of the Kings of Britain, helping to kick-start many of the myths that surround this city!

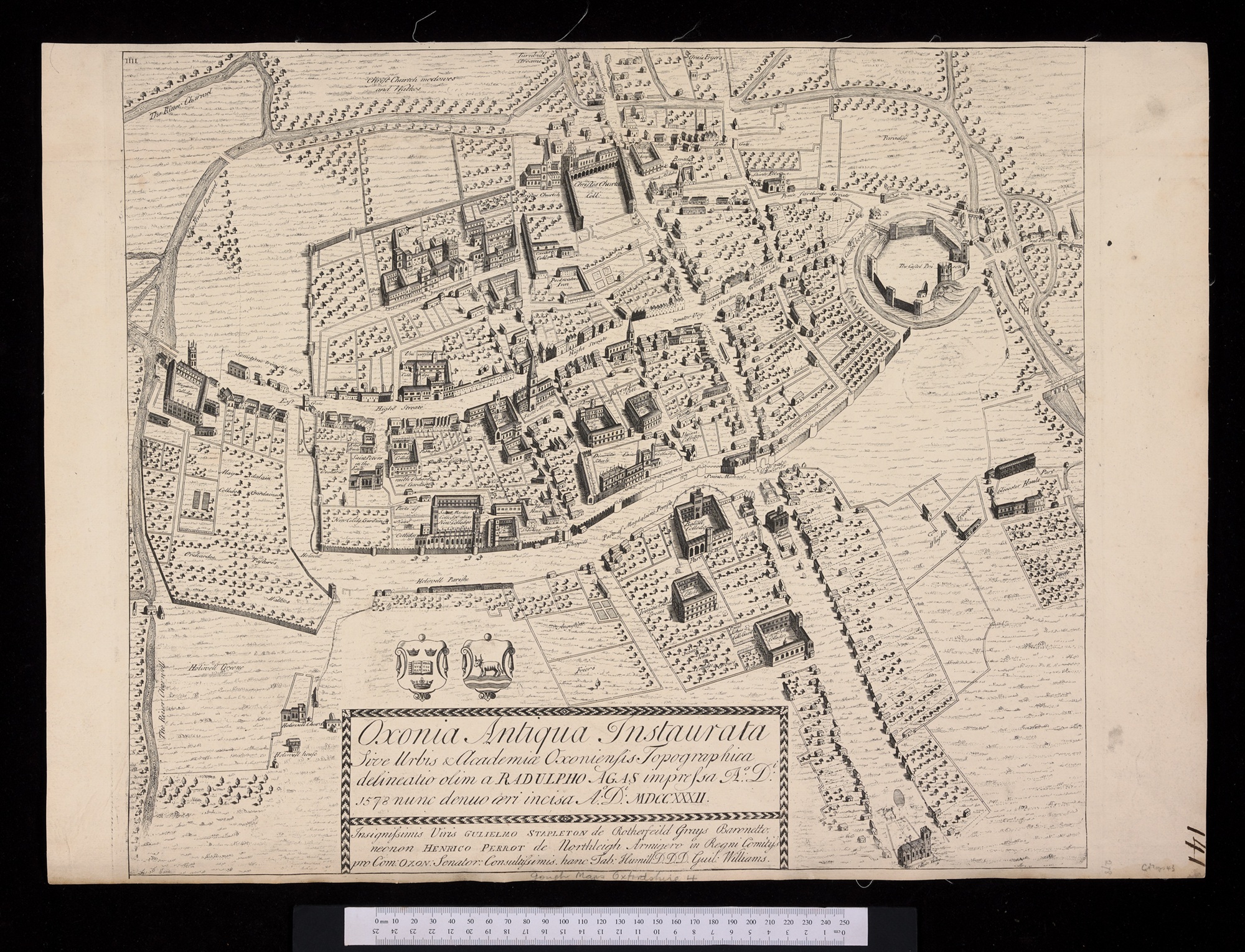

Featured image: Bodleian Library Gough Maps Oxfordshire 4

Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

John Blair ‘St Frideswide Reconsidered’, Oxoniensia, Vol. 52, (1987)

Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford: A history of the city by Janet Cooper’, in Alan Crossley (eds), The Victoria History of the County of Oxford Volume IV, (London, 1979)

James Parker, The Early History of Oxford: 727-1000, (Oxford 1885)

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, ed. J.A. Giles, (London, 1914)

[1] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, ed. J.A. Giles, (London, 1914), p. 67.

[2] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford: A history of the city by Janet Cooper’, in Alan Crossley (eds), The Victoria History of the County of Oxford Volume IV, (London, 1979), p.5.

[3] James Parker, The Early History of Oxford: 727-1000, (Oxford 1885), p. 142

[4] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford: A history of the city’, p. 5,

[5] John Blair ‘St Frideswide Reconsidered’, Oxoniensia, Vol. 52, (1987), p. 88.

[6] James Parker, Early History of Oxford: 727-1000, (Oxford 1885),

[7] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 18-19.

[8] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 13.

[9] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 10, 14, 16.

[10] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 6-7.

[11] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 5-6.

[12] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 5-6.

[13] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 24.

[14] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 9.

[15] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 26-27.

[16] James Parker, Early History of Oxford, pp. 62.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| PHPSESSID | session | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_UA-9822230-4 | 1 minute | A variation of the _gat cookie set by Google Analytics and Google Tag Manager to allow website owners to track visitor behaviour and measure site performance. The pattern element in the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. |

| _gcl_au | 3 months | Provided by Google Tag Manager to experiment advertisement efficiency of websites using their services. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _fbp | 3 months | This cookie is set by Facebook to display advertisements when either on Facebook or on a digital platform powered by Facebook advertising, after visiting the website. |

| fr | 3 months | Facebook sets this cookie to show relevant advertisements to users by tracking user behaviour across the web, on sites that have Facebook pixel or Facebook social plugin. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |