aaa

aaa

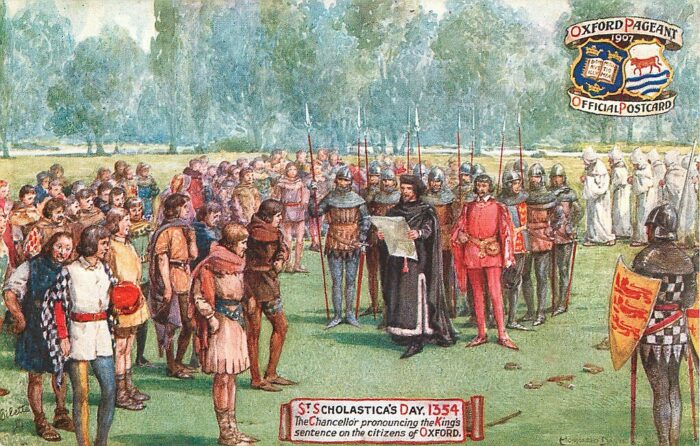

The rivalry between the university and the city of Oxford is, for the most part light-hearted today, but it was nothing short of extremely violent back in the Middle Ages. It culminated in some of the bloodiest days in the town’s history, including the St Scholastica Day riot of 1355. But how did the rivalry escalate into such violence?

Oxford in the Middle Ages was initially important as a market town, so prosperous was it that it paid the third highest tallage in England by the thirteenth century. At the same time, it was increasingly becoming a centre of learning. From at least 1096, students were studying in the town, including at the Collegiate Chapel of St. George located inside the castle walls.

As war with France prevented students from studying in the University of Paris, Oxford became the place to study. By the 13th century, this brought a large population of students and scholars to the town, leading to friction.

The power early medieval universities had was considerable; in the case of Oxford, it came to control the town market and much of the property inside the walls. There were also legal privileges, and students had the same rights as clergy, meaning they could only be tried in ecclesiastical courts and not by town authorities. The townspeople felt they were above the law, and in many ways, they were.

Robberies, attacks and murders were common among the students, and understandably, the townspeople fought back. In 1209, two scholars of the university were lynched by a mob, causing a considerable portion of scholars and students to flee to Cambridge, setting up the university there as a result. These tensions were heightened by the decline of Oxford during the fourteenth century, partially a result of the Black Death but also as the town increasingly relied on the university as a source of income.

All of this came to a head on the 10th of February 1355. In an incident at the Swindlestock Tavern, students attacked the landlord over poor wine and service, leading to a brawl between students and townspeople. Whilst calls for calm were made, including by the university’s chancellor, things quickly got out of hand.

In the subsequent 48 hours, the town bailiffs armed the people and encouraged a mob to attack students and scholars. This even included people from the surrounding countryside, enticed by the money offered by the bailiffs.

To cries of “Havoc! Havoc! Smyt fast, give gode knocks!” the townspeople broke into taverns and halls of residence. Students and other members of the university fled or barricaded themselves inside their colleges or inside the Augustine Priory in the town. Those who didn’t were killed by the townspeople.

Students and scholars were allegedly scalped so as to look like the clergy they had the privileges of, and thrown into dunghills or the River Thames. Despite intervention by King Edward III, who was staying in nearby Woodstock, it would take two whole days before the violence finally began to subside. The total number of people killed is unclear, but it’s likely to be around thirty townspeople, sixty students and scholars.

The town may have won the day, with most student halls and colleges destroyed, but the university would eventually prevail. As with previous incidents, the King sided with the students and the town was punished heavily. The townspeople were not only fined and the mayor imprisoned, but in June, the university was given a charter granting it considerable commercial rights. These included the right to tax bread and alcohol sold in town, which allowed the university to dominate commerce.

To add insult to injury, the mayor and other prominent townspeople had to also attend an annual mass commemorating the deaths of the students, a practice which did not end until 1825. In the end, the riot guaranteed the university’s power in Oxford and led to a long decline in the town’s fortunes during the Later Middle Ages.

But the riot didn’t end the rivalry. Incidents between town and gown would continue, though to nowhere near the same level of violence as had occurred on St Scholastica’s Day. The students within the castle walls have long gone, but you can come and see one of Oxford’s first centres of learning at our site, as well as one of the places students used to be locked up!

[1] Anne Dodd (eds), Oxford before the University, (Oxford, 2003).

[2] Janet Cooper, ‘Medieval Oxford: A history of the city by Janet Cooper’, in Alan Crossley (eds), The Victoria History of the County of Oxford Volume IV, (London, 1979).

[3] Mark Davies, Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Dunghill, (Towpath, 2005).

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| PHPSESSID | session | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_UA-9822230-4 | 1 minute | A variation of the _gat cookie set by Google Analytics and Google Tag Manager to allow website owners to track visitor behaviour and measure site performance. The pattern element in the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. |

| _gcl_au | 3 months | Provided by Google Tag Manager to experiment advertisement efficiency of websites using their services. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _fbp | 3 months | This cookie is set by Facebook to display advertisements when either on Facebook or on a digital platform powered by Facebook advertising, after visiting the website. |

| fr | 3 months | Facebook sets this cookie to show relevant advertisements to users by tracking user behaviour across the web, on sites that have Facebook pixel or Facebook social plugin. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |